Parallel history – 1587

Traditional teaching of history was boring and myopic. Much of it still is. Lists of dates, rulers and ‘events’ give us facts – if we remember them. Studies of individuals and social attitudes add colour. We appreciate eminent scholars who write in depth about specific events and times. Yes, specialisation is essential.

However, the history of one period, people, culture, or country is narrow and nationalistic. We must broaden our scope if we are to understand the world. After all, ever since humans walked, they have travelled the world. By studying history only from the point of view of one culture, we risk ignoring the influence of others. We also risk the arrogance of believing that our version of history is right.

We need to know what was happening in other places and to other people. We need parallel history. Parallel history covers what happened around the world at the same time. Another definition is to describe events from different points of view. In this first-in-series, we focus on 1587 CE. It seems to have been an unhappy year in several places.

China

In his famous book, “1587 – a year of no significance”, Professor Ray Huang gives a vivid picture of a year in the life of China’s famous Ming dynasty. Lasting until 1644, the Ming dynasty overthrew the Mongol Yuan dynasty in 1368. For much of its duration, the Ming Emperors were very successful. Wan Li, the Emperor in 1587, lived a life of ritual and bureaucracy.

The court observed the proper, long-standing, rules. If it did not, failure was bound to result. Founded on Confucian principles, court life was ordered, secure and apparently would never change.

But, unbeknownst to anyone at the time, the Ming dynasty was already in decline.

Wan Li was lazy, inexperienced, and left everything to courtiers who fought among themselves. Hai Jui, a popular official trying to stop corruption, was impeached by his fellow officials, and died disgraced. General Chang Chu-cheng fought for years to modernise the Emperor’s army. Civil servants accused him of violating the bureaucratic principle of ‘balance’. He died alone and destitute in 1588, the year the Spanish Armada failed to conquer England. Li Chi, the Luther of his culture, who tried to champion greater freedom of thought, was tried for what amounted to sedition. While in jail, disgraced, he slit his throat with a borrowed razor.

“The year 1587 may seem insignificant,” concludes Professor Huang. “Nevertheless…the time limit for the Ming dynasty had already been reached. 1587 must go down in history as a chronicle of failure.”

England

10,000 kilometres to the west of Beijing, another tragedy concluded in 1587. Queen Elizabeth I of England was a staunch member of the new religion, Protestantism. Her rival, Mary, was a staunch Roman Catholic, the traditional religion of Europe. Elizabeth was Queen of England. Mary was Queen of Scotland and had a claim to the English throne.

Each queen had a large court. Court members believed they acted in the best interests of their Queen, their religion and country – and of course themselves. As each group of courtiers jostled for position and influence, men were killed, battles fought, and plots alleged. Each queen claimed to have God on their side. Each had their spies and agents.

From 1561 when she became Queen of Scotland, until Mary’s death in 1587, both courts twisted and turned to get the upper hand. Proposals to compromise came from both sides. But enmity between the two religions ensured there would be no peace between them.

Perceiving Mary as a threat, Elizabeth had her confined in various castles and manor houses in the interior of England. After years in custody, the High court found Mary guilty of plotting to assassinate Elizabeth in 1586.

The Court convicted Mary on 25 October 1586 and sentenced her to death. Nevertheless, Elizabeth hesitated to order the execution, even in the face of pressure from the English Parliament. She was concerned that the killing of a queen set a bad precedent. However, on the evening of 7 February 1587, Mary knew she was to be beheaded the next morning.

The execution was flawed. And in a final bizarre episode, when the executioner lifted the head to display it, its hair detached. Mary’s long red hair turned out to be a wig. She had short cropped grey hair.

Elizabeth protested that her order had been misunderstood and she never intended the execution to take place. In a reign of many successes, the beheading of Mary Queen of the Scots left a stain on Elizabeth’s legacy.

Roanoke – North America

The first settlement by Europeans in North America took place when ‘The Pilgrim Fathers’ established the city of Plymouth in 1620 CE. However, decades before, in 1587, another group of settlers had tried to do the same.

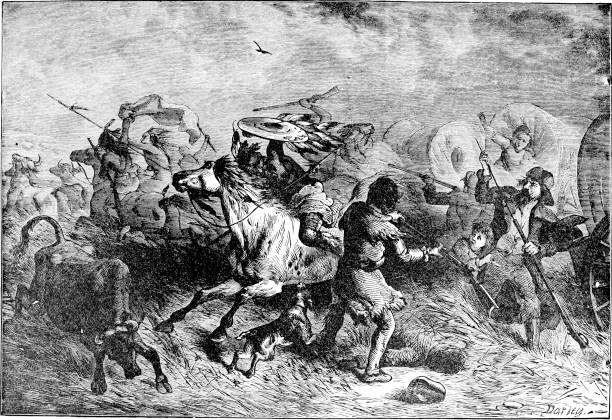

Roanoke is a small island on the coast of what is now North Carolina in the United States of America. Explorer Sir Walter Raleigh founded the Roanoke Island colony in August 1585. It was the first English settlement in the New World. The Roanoke colonists suffered from dwindling food supplies and attacks from local people. In 1586 they returned to England aboard a ship captained by Sir Francis Drake. In 1587, Raleigh sent out another group of 100 colonists under a certain John White. White returned to England to get more supplies, but a war with Spain delayed his return to Roanoke. By the time he finally returned in August 1590, everyone had vanished.

For the last 400 years, historians and scientists have speculated about what happened. To this day, there is no sure evidence. Theories about wars with native Americans are common. Moving to another island (Hatteras is often cited) is another. Starvation and decline seem an obvious possibility.

This year (2020) a new book about the colonists, “The Lost Colony and Hatteras Island,” tries to solve the mystery with archaeology. The book’s author argues that the native people who lived there took in the English settlers. He believes that historical records and artifacts can end the debate. The archaeological evidence is that that they went to Hatteras. However, even the book’s publishers do not seem convinced. “Archaeologists from the University of Bristol, working with the Croatoan (the old name for Hatteras) Archaeological Society, have uncovered tantalizing clues (my italics) to the fate of the colony.”

It is hardly the definitive answer to solve a 400-year-old mystery.

Conclusions

What links these three episodes in history apart from the date? Well, they were all failures. The Ming Emperor chose not to see what was happening in his court. Elizabeth I failed to keep alive her ‘sister’ queen. And the settlers of Roanoke failed to found a new colony (so far as we know).

Life can be random. It is unpredictable while we live it. The Emperor almost certainly could not have foreseen the demise of the Ming dynasty and his contribution to it. Queen Mary might or might not have agreed to a plot to assassinate Queen Elizabeth. But she failed to see what was happening around her. Elizabeth seems to have been more aware (or had better spies) but even she was unhappy when Mary’s execution took place. The reality came as a surprise.

When John White – and every researcher since – returned to Roanoke, no-one could have foreseen the disappearance of 100 people. They vanished without a trace. Even the latest archaeological and historical research have unearthed no more than partial evidence to support one theory.

However careful humans are to plan their future, chaos theory will ensure that nothing works as forecast.

Worked on the article:

Wanlikhang